- Home

- David Sedaris

Let's Explore Diabetes With Owls

Let's Explore Diabetes With Owls Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

To my sister Amy

Author’s Note

Over the years I’ve met quite a few teenagers who participate in what is called “Forensics.” It’s basically a cross between speech and debate. Students take published short stories and essays, edit them down to a predetermined length, and recite them competitively. To that end, as part of the “Etc.” in this book’s subtitle, I have written six brief monologues that young people might deliver before a panel of judges. I believe these stories should be self-evident. They’re the pieces in which I am a woman, a father, and a sixteen-year-old girl with a fake British accent.

Dentists Without Borders

One thing that puzzled me during the American health-care debate was all the talk about socialized medicine and how ineffective it’s supposed to be. The Canadian plan was likened to genocide, but even worse were the ones in Europe, where patients languished on filthy cots, waiting for aspirin to be invented. I don’t know where these people get their ideas, but my experiences in France, where I’ve lived off and on for the past thirteen years, have all been good. A house call in Paris will run you around fifty dollars. I was tempted to arrange one the last time I had a kidney stone, but waiting even ten minutes seemed out of the question, so instead I took the subway to the nearest hospital. In the center of town, where we’re lucky enough to have an apartment, most of my needs are within arm’s reach. There’s a pharmacy right around the corner, and two blocks farther is the office of my physician, Dr. Médioni.

Twice I’ve called on a Saturday morning, and, after answering the phone himself, he has told me to come on over. These visits too cost around fifty dollars. The last time I went, I had a red thunderbolt bisecting my left eyeball.

The doctor looked at it for a moment, and then took a seat behind his desk. “I wouldn’t worry about it if I were you,” he said. “A thing like that, it should be gone in a day or two.”

“Well, where did it come from?” I asked. “How did I get it?”

“How do we get most things?” he answered.

“We buy them?”

The time before that, I was lying in bed and found a lump on my right side, just below my rib cage. It was like a deviled egg tucked beneath my skin. Cancer, I thought. A phone call and twenty minutes later, I was stretched out on the examining table with my shirt raised.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” the doctor said. “A little fatty tumor. Dogs get them all the time.”

I thought of other things dogs have that I don’t want: Dewclaws, for example. Hookworms. “Can I have it removed?”

“I guess you could, but why would you want to?”

He made me feel vain and frivolous for even thinking about it. “You’re right,” I told him. “I’ll just pull my bathing suit up a little higher.”

When I asked if the tumor would get any bigger, the doctor gave it a gentle squeeze. “Bigger? Sure, probably.”

“Will it get a lot bigger?”

“No.”

“Why not?” I asked.

And he said, sounding suddenly weary, “I don’t know. Why don’t trees touch the sky?”

Médioni works from an apartment on the third floor of a handsome nineteenth-century building, and, on leaving, I always think, Wait a minute. Did I see a diploma on his wall? Could “Doctor” possibly be the man’s first name? He’s not indifferent. It’s just that I expect a little something more than “It’ll go away.” The thunderbolt cleared up, just as he said it would, and I’ve since met dozens of people who have fatty tumors and get along just fine. Maybe, being American, I want bigger names for things. I also expect a bit more gravity. “I’ve run some tests,” I’d like to hear, “and discovered that what you have is called a bilateral ganglial abasement, or, in layman’s terms, a cartoidal rupture of the venal septrumus. Dogs get these all the time, and most often they die. That’s why I’d like us to proceed with the utmost caution.”

For my fifty dollars, I want to leave the doctor’s office in tears, but instead I walk out feeling like a hypochondriac, which is one of the few things I’m actually not. If my French physician is a little disappointing, my French periodontist more than makes up for it. I have nothing but good things to say about Dr. Guig, who, gumwise, has really brought me back from the abyss. Twice in the course of our decadelong relationship, he’s performed surgical interventions. Then, last year, he removed four of my lower incisors, drilled down into my jawbone, and cemented in place two posts. First, though, he sat me down and explained the procedure, using lots of big words that allowed me to feel tragic and important. “I’m going to perform the surgery at nine o’clock on Tuesday morning, and it should take, at most, three hours,” he said—all of this, as usual, in French. “At six that evening, you’ll go to the dentist for your temporary implants, but still I’d like you to block out that entire day.”

I asked my boyfriend, Hugh, when I got home, “Where did he think I was going to go with four missing teeth?”

I see Dr. Guig for surgery and consultations, but the regular, twice-a-year deep cleanings are performed by his associate, a woman named Dr. Barras. What she does in my mouth is unspeakable, and because it causes me to sweat, I’ve taken to bringing a second set of clothes and changing in the bathroom before I leave for home. “Oh, Monsieur Sedaris,” she chuckles. “You are such a child.”

A year ago, I arrived and announced that, since my previous visit, I’d been flossing every night. I thought this might elicit some praise—“How dedicated you are, how disciplined!”—but instead she said, “Oh, there’s no need.”

It was the same when I complained about all the gaps between my teeth. “I had braces when I was young, but maybe I need them again,” I told her. An American dentist would have referred me to an orthodontist, but, to Dr. Barras, I was just being hysterical. “You have what we in France call ‘good time teeth,’” she said. “Why on earth would you want to change them?”

“Um, because I can floss with the sash to my bathrobe?”

“Hey,” she said, “enough with the flossing. You have better ways to spend your evenings.”

I guess that’s where the good times come in.

Dr. Barras has a sick mother and a long-haired cat named Andy. As I lie there sweating with my trap wide open, she runs her electric hook under my gum line, and catches me up on her life since my last visit. I always leave with a mouthful of blood, yet I always look forward to my next appointment. She and Dr. Guig are my people, completely independent of Hugh, and though it’s a stretch to label them friends, I think they’d miss me if I died of a fatty tumor.

Something similar is happening with my dentist, Dr. Granat. He didn’t fabricate my implants—that was the work of a prosthodontist—but he took the molds and made certain that the teeth fit. This was done during five visits in the winter of 2011. Once a week, I’d show up at the office and climb into his reclining chair. Then I’d sink back with my mouth open. “Ça va?” he’d ask every five minutes or so, meaning, “All right?” And I’d release a little tone. Like a doorbell. “E-um.”

Implants come in two stages. The first teeth that get screwed in, the temporaries, are blocky, and

the color is off. The second ones are more refined and are somehow dyed or painted to match their neighbors. My four false incisors are connected to form a single unit and were secured into place with an actual screwdriver. Because the teeth affect one’s bite, the positioning has to be exact, so my dentist would put them in and then remove them to make minor adjustments. Put them in, take them out. Over and over. All the pain was behind me by this point, so I just lay there, trying to be a good patient.

Dr. Granat keeps a small muted television mounted near the ceiling, and each time I come it is tuned to the French travel channel—Voyage, it’s called. Once, I watched a group of mountain people decorate a yak. They didn’t string lights on it, but everything else seemed fair game: ribbons, bells, silver sheaths for the tips of its horns.

“Ça va?”

“E-um.”

Another week we were somewhere in Africa, where a family of five dug into the ground and unearthed what looked to be a burrow full of mice. Dr. Granat’s assistant came into the room to ask a question, and when I looked back at the screen the mice had been skinned and placed, kebab-like, on sharp sticks. Then came another distraction, and when I looked up again the family in Africa were grilling the mice over a campfire, and eating them with their fingers.

“Ça va?” Dr. Granat asked, and I raised my hand, international dental sign language for “There is something vital I need to communicate.” He removed his screwdriver from my mouth, and I pointed to the screen. “Ils ont mangé des souris en brochette,” I told him, meaning, “They have eaten some mice on skewers.”

He looked up at the little TV. “Ah, oui?”

A regular viewer of the travel channel, Dr. Granat is surprised by nothing. He’s seen it all and is quite the traveler himself. As is Dr. Guig. Dr. Barras hasn’t gone anywhere exciting lately, but what with her mother, how can she? With all these dental professionals in my life, you’d think I’d look less like a jack-o’-lantern. You’d think I could bite into an ear of corn, or at least tear meat from a chicken bone, but that won’t happen for another few years, not until we tackle my two front teeth and the wobbly second incisors that flank them. “But after that’s done I’ll still need to come regularly, won’t I?” I said to Dr. Guig, almost panicked. “My gum disease isn’t cured, is it?”

I’ve gone from avoiding dentists and periodontists to practically stalking them, not in some quest for a Hollywood smile but because I enjoy their company. I’m happy in their waiting rooms, the coffee tables heaped with Gala and Madame Figaro. I like their mumbled French, spoken from behind Tyvek masks. None of them ever call me David, no matter how often I invite them to. Rather, I’m Monsieur Sedaris, not my father but the smaller, Continental model. Monsieur Sedaris with the four lower implants. Monsieur Sedaris with the good-time teeth, sweating so fiercely he leaves the office two kilos lighter. That’s me, pointing to the bathroom and asking the receptionist if I may use the sandbox, me traipsing down the stairs in a fresh set of clothes, my smile bittersweet and drearied with blood, counting the days until I can come back and return myself to this curious, socialized care.

Attaboy

It was winter and I was in New York, killing time before a movie. Week-old snow lay moldering along the curbs, and I was just noticing all the trash in it when I heard a man yell, “Citizen’s arrest!” I guess I knew that such a thing existed, but you never hear of anyone taking advantage of it, so I assumed it was a joke—a candid-camera type of thing, or maybe a student making a movie.

“Citizen’s arrest!” the man repeated. He was standing in front of a grocery store called Fairway, on Broadway and 74th. Neat, pewter-colored hair covered the back and sides of his head, but the top of it was bald and raw-looking from the cold. The man had a puffy down jacket on, and as I moved closer, I saw that he was touching the shoulder of a teenage boy, not gripping him so much as tagging him, claiming him.

“Citizen’s arrest. Citizen’s arrest!” I wondered what crime had been committed, and, judging from the people around me, many of whom had stopped or at least slowed down, I wasn’t alone. Something silver had dropped to the ground, and just as I saw that it was a Magic Marker, a couple ran out of the store—the boy’s parents, I assumed, for they raced right to his side. “Citizen’s arrest,” the man repeated. “He was graffitiing the mailbox!”

I expected the parents to say, “He was what?” But rather than scolding their guilty-looking son, they turned on the guy who had caught him. “Who gave you the right to touch our child?”

“But the mailbox,” the man explained, “I saw him—”

“I don’t care what he was doing,” the woman said. “You have no right touching my son.” She made it sound like a sexual thing, like he’d had his hand up the boy’s ass rather than resting, weightless, on his shoulder. “Just who the hell do you think you are?” She turned to her husband. “Douglas, call the police.”

“I’m two steps ahead of you,” he said.

Watching him dial, I thought, Really? This is your reaction? If I were thirteen and I’d been caught graffitiing a mailbox, my parents would have thanked the man and shaken his hand. “We’ll take it from here,” they’d have assured him. Then, in full view of the crowd, they would have beaten me—not a couple of light stage slaps but the real thing, with loosened teeth and muffled pleas for mercy. And that would have been just the start of it. Not only would my allowance have been cut off, but if I ever wanted freedom again, I’d have had to pay for it: every hour outside my room costing me a dollar, which is like, I don’t know, seventeen dollars in today’s currency.

“But how do you expect me to work if I can’t go outside?” I’d have wept.

“You should have thought about that before you defaced that mailbox,” my father would have told me, this while my mother held my arms behind my back and he hit me with a golf club. In the balls.

Never would they have blindly defended me or even asked for my side of the story, as that would have put me on the same level as the adult. If a strange man accused you of doing something illegal, you did it. Or you might as well have done it. Or you were at least thinking about doing it. There was no negotiating, no “parenting” the way there is now. All these young mothers chauffeuring their volcanic three-year-olds through the grocery store. The child’s name always sounds vaguely presidential, and he or she tends to act accordingly. “Mommy hears what you’re saying about treats,” the woman will say, “but right now she needs you to let go of her hair and put the chocolate-covered Life Savers back where they came from.”

“No!” screams McKinley or Madison, Kennedy or Lincoln or beet-faced baby Reagan. Looking on, I always want to intervene. “Listen,” I’d like to say, “I’m not a parent myself, but I think the best solution at this point is to slap that child across the face. It won’t stop its crying, but at least now it’ll be doing it for a good reason.”

I don’t know how these couples do it, spend hours each night tucking their kids in, reading them books about misguided kittens or seals who wear uniforms, and then rereading them if the child so orders. In my house, our parents put us to bed with two simple words: “Shut up.” That was always the last thing we heard before our lights were turned off. Our artwork did not hang on the refrigerator or anywhere near it, because our parents recognized it for what it was: crap. They did not live in a child’s house, we lived in theirs.

Neither were we allowed to choose what we ate. I have a friend whose seven-year-old will only consider something if it’s white. Had I tried that, my parents would have said, “You’re on,” and served me a bowl of paste, followed by joint compound, and, maybe if I was good, some semen. They weren’t considered strict by any means. They weren’t abusive. The rules were just different back then, especially in regard to corporal punishment. Not only could you hit your own children, but you could also hit other people’s. I was in the fifth grade when someone on our street called my mother a bitch. “I wasn’t doing anything out of the ordinary,” she said to my father

. “Just driving Lisa home from her doctor’s appointment, and out of nowhere this boy yelled it out.” Four months pregnant with my brother, Paul, she lit a cigarette and poured herself some wine from the fifty-gallon jug beside the toaster.

“What boy?” my father asked. He had just returned from work and was standing in the kitchen, drinking a glass of gin with some ice in it. Before him on the counter were crackers and a rectangle of cream cheese smothered in golden sauce. “Oh no, you don’t,” he said as I reached for the knife. “This is for me, goddamnit.”

“But can’t I just—”

“You want an after-work snack, get a job,” he said, forgetting, I guess, that I was eleven.

“So who’s this kid who called your mother a bitch?” he asked. “Give me his name so I can go talk to him.”

I said I didn’t know, and he looked at me with disappointment, the way you might at anyone who was woefully unconnected. “Well, can’t you at least guess?”

“Beats me.” No one on our street had reason to hate my mother. It was likely someone just road testing his new curse word—a little late too, as our end of the block had discovered it months earlier. “It means ‘female dog,’” I’d explained to my sisters, “but it also means ‘a woman who’s crabby and won’t let you be yourself.’”

The day that someone called my mother a bitch was not remarkable. My father returned from work, like always. He had his drink and his fancy snack. When my mother announced dinner, he took off his jacket, stepped out of his trousers, and took his seat alongside the rest of us. From the tabletop up, he was all business casual—the ironed shirt, the loosened tie—but from there on down it was just briefs and bare legs. “So I understand from your mother that someone called her a not very nice word this afternoon,” he said, turning to my older sister. “You were in the car with her. Any idea who it was?”

Me Talk Pretty One Day

Me Talk Pretty One Day Calypso

Calypso Holidays on Ice

Holidays on Ice Mi vida en rose

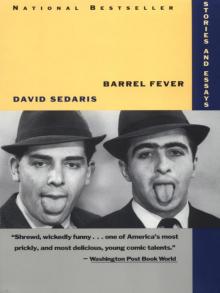

Mi vida en rose 1994 - Barrel Fever

1994 - Barrel Fever Naked

Naked Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim

Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim When You Are Engulfed in Flames

When You Are Engulfed in Flames Theft by Finding: Diaries 1977-2002

Theft by Finding: Diaries 1977-2002 Let's Explore Diabetes With Owls

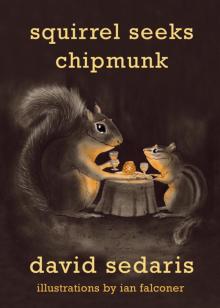

Let's Explore Diabetes With Owls Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk: A Modest Bestiary

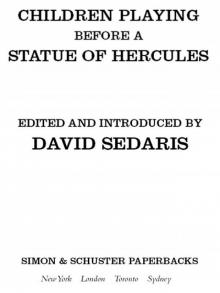

Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk: A Modest Bestiary Children Playing Before a Statue of Hercules

Children Playing Before a Statue of Hercules The Best of Me

The Best of Me Barrel Fever

Barrel Fever Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk

Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk Theft by Finding

Theft by Finding Barrel Fever and Other Stories

Barrel Fever and Other Stories